I hear the Westminster Quarters chime even when I’m not at my apartment. This occurs to me indirectly, over a pint of Guinness at a seedy bar in a town that didn’t have churches that chimed on the hour. And if it did, I was pretty certain that no one appreciated it the way I do. No one’s internal metronome was set to it the way mine is.

"It’s 8:00," I say to my companion, for no real reason. The day’s last chime played like elevator music in my brain, and I felt compelled for someone to notice the change, as if it were a matter of vital importance. People in seedy bars don’t notice the passing of time. I looked around. There wasn’t even a clock on the wall.

I got up to go to the bathroom, leaving Dylan to emptily watch the bartender uncap a row of Bud Lights. That’s the kind of bar this was. The most popular drink was bottled Bud Light.

Inside the bathroom, I stared momentarily at the confluence of red walls and red clay tiling. It seemed extraneously unnecessary and I got angry that money was spent by someone trying to make this bathroom look like something other than what it was, which was a restroom of an awful bar in a small New England city losing its soul. Turning away from the visuals that were upsetting me, I decided to wash my hands. It seemed like an appropriate enough thing to do in a bathroom, really, since I had no intentions of emptying my bladder or powdering my nose or whatever else females do inside of bathrooms.

Two girls then fell through the door and one pushed the other up against the angry red wall. "I’m pissed at you for saying that," she said, but it sounds too passive to me. Like she wasn’t upset but had to feign being so in order to still be accepted in whatever social circle she thought she belonged to.

"What did I say?" the other girl asked, genuinely surprised. I dried my hands on a bandana that hung from my back pocket and quickly exited.

"Two girls were fighting in the bathroom," I said to Dylan when I returned.

"Really?" he asked, interested. I think he must have been a little drunk, as that sort of announcement shouldn’t come to anyone’s surprise given the company here. Girls’ ribcages poked out unnaturally, and every man in here had the starts of a beer belly and wore a rugby style shirt. Half-heartedness was the basis for all their relationships, I was pretty sure. Relationships with food and beer included.

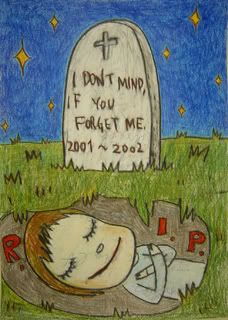

"Can we leave?" I asked after downing the rest of my Guinness. "Rugby shirts make me nervous and this town feels like a huge empty graveyard."

"It wasn’t so long ago that you lived here yourself, you know," he pointed out. "And might I add, you love graveyards."

I nodded willfully but said nothing. He paid the tab, finished his murky drink and we filed through a loud, wobbly congregation of guys wearing Red Sox hats. I felt their eyes on us, watching how I held his hand, with the interest that children give to neat colorful rows of candy. Empty, passing longing.

The night air felt good but I didn’t breathe it in deeply. I didn’t want this foreign, dirty air in my lungs. I didn’t want to need it even in the most basic of ways.

'It’s not my home," I said flatly. Dylan seemed to understand that I was continuing our conversation from inside the bar, though a few minutes had passed and he was surely thinking of other things.

"Goddamnit, does a place have to have some immense emotional connection to you for you to have a good time in it? You lived here, and you ate dinner with your neighbor and held her child while watching movies. Doesn’t that stick to you?"

"It isn't their true home, either," I replied.

"I live here," he said, defensively. "Don’t I matter?"

I said nothing to this, but looked wearily at Dylan as we walked briskly up the sidewalk. It might have been cold, or it might not have been.

"Let’s go to your place. We can argue your existential crisis on your porch and wave to every car that passes by, and I’ll listen as you list off the occupants’ names once they pass by." He sounded bitter about this; as if by knowing people I was somehow a less-civilized person than he. I didn’t reply but we got into my car and I drove swiftly to my apartment.

I exhaled deeply when I reached the town line, and Dylan looked at me quizzically. I slowed down and pulled off the state highway to drive the long way through town, drinking in the images of all the houses with curtains drawn. The town’s ‘downtown,’ if you could call it that, was set up like an avenue, with a vast green between the two parallels. One side of the green had things like the old church, the town hall, and a small cemetery with names on the stones of people still living. The town’s noblemen, painters, oil guys. The other side, the side I drove down, had mostly houses and one small row of shops. That’s where the green closed itself, punctuated with a huge, sprawling house. The two parallels diverged here, still running parallel but no longer with open space between them.

Pulling into my building’s parking lot, Dylan glanced to the Masonic building across the street, where the lights glowed from one of the second-floor windows.

"Sewing club meeting," I answered, though he hadn’t asked. He sighed, frustrated maybe. I could see Mrs. Tamillo’s head bobbing back and forth inside the window.

Dylan got out of the car anxiously, heading for my door. I treaded softly and resented that he had probably scared off my nighttime friends with his loud gait. Many nights I see eyes glowing from under the shed, or shadows dart towards the trees, stopping to sniff the air. If I am quiet enough nothing darts, they just go along with the important business of animals, hesitating momentarily when the wind shifts and they catch my scent, but quickly registering that I won’t bother them.

That’s one thing that binds me here. The woodchucks know my scent. The mink that slinks around by the lake doesn’t run from me. It’s as if I am a necessary part of the ecology here. As natural and indispensable as air.

We went inside, and never ended up back out on the porch. Thinking about the important business of animals drew me to Dylan’s skin, where a crucial collision of bones relinquished the sour mood brought on by the huge empty graveyard of Haverhill.

"I like graveyards that aren’t empty," I explained in the morning, when the sound of chickadees and robins outside my widow forced consciousness upon Dylan and I.

Dylan was remarkable at following these mental pathways of mine. He always seemed to be riding the same frequency as I was, progressing with thought in the same pattern as I did.

"What makes a graveyard empty as opposed to full?" he asked legitimately.

I furrowed my brow for a moment, comparing my favorite place to my least favorite. "An empty graveyard is like the ocean, plenty of things residing under there but nothing interesting to look at."

"That sounds like every great city I’ve ever been to," he sighed into my neck, and maybe he was right.

I thought about geese honking as they fly and about the millions of mosquitoes that starve to death each day, never finding a warm blooded creature to feed on. Overwhelmed with sorrow for those mosquitoes, irrational as it was, prompted me to ask Dylan why he was here.

"What do you mean? To be with you," he replied without opening his eyes. I followed the bumps of his vertebrae with my fingertips.

I didn’t comment on that. It seemed honest enough of an answer, though maybe I had hoped for more. Our arrangement was gnawing at my muscle so that I seemed starved. I skulked around some days like a hungry lion, ashamed of my ribcage. I wished Dylan would feel unsure, too, but he was a less prideful sort of creature. He held himself with the mindful self-assurance of a grizzly. Even in the hungry months, he was not uncomfortable with what he was.

He was not uncomfortable with what we were, and yet I couldn't stop thinking he was like a mosquito, searching for proper sustenance, which I knew he couldn't find in me.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment